deacon brodie

The real story behind Edinburgh's most enduring legend

Williamson's Edinburgh Directory

Williamson's Directory for the City of Edinburgh became a staple publication for residents of the metropolis after it was first compiled in 1773. Created by the colorful Peter Williamson (1730 – 19 January 1799), who was known locally as “Indian Peter,” the listing was made up of the addresses of merchants, officials, lawyers, bankers, shops, taverns, and any other noteworthy person of business in the city. The publication sold for a shilling and was published at regular intervals until 1796. Today, Williamson’s efforts are a boon for historians and those charting genealogies. Keep in mind that Williamson’s directories do not include everyone that lived in Edinburgh during those years. Only those who had a certain social standing or businesses made the directory’s cut. Still Williamson's Edinburgh directories are an invaluable tool for examining certain aspects of Edinburgh life during the time of Deacon Brodie.

The National Library of Scotland has graciously digitized a few volumes of Williamson’s directory and released those texts under a Creative Commons 2.5 UK: Scotland license. The following volumes are presented on this site:

- Williamson's Edinburgh Directory, from May 1773, to May 1774

- Williamson's Edinburgh Directory, from May 1774, to May 1775

- Williamson's Edinburgh Directory, from June 1784, to June 1785

- Williamson's Edinburgh Directory, from June 1786, to June 1788

- Williamson's Edinburgh Directory, from June 1788, to June 1790

- Williamson's Edinburgh Directory, from June 1790, to June 1792

About Peter Williamson

Peter Williamson was a contemporary of Deacon Brodie and it is likely the two men knew each other. Brodie would have been drawn to Williamson’s bizarre life story. An eight-year-old Williamson was abducted from the quay at Aberdeen, taken to Philadelphia, and sold into a seven-year indentured servant contract. By the age of twenty-four, Williamson had earned his freedom and married the daughter of a wealthy plantation owner only to have tragedy strike again. A Cherokee Indian raid on his property left his farm burned, wife dead, and captured by the Cherokee. Williamson was a human pack mule for the Cherokee for several months before escaping and returning to Philadelphia. There he enlisted in an English Army regiment and fought two years in the French and Indian War rising to the rank of Lieutenant.

Ill fortune continued to follow Peter Williamson as he was once again captured by members of the French Army. While being held prisoner in Quebec, Lieutenant Williamson was granted parole as an exchange prisoner and shipped to Plymouth, England arriving in November of 1756. There Williamson was discharged from the Army, due to a hand injury, and given muster out pay of six shillings. With that small stipend, Williamson set off walking from Plymouth back to Aberdeen. He was destitute by the time he reached York, but found folks liked listening to his tales of captivity. He caught the eye of some of York’s socialites who suggested Williamson write an account of his life. With their support, Williamson wrote French and Indian Cruelty, Exemplified in the Life and various Vicissitudes of Fortune of Peter Williamson, Who was Carried off from Aberdeen in his Infancy and Sold as a Slave in Pennsylvania and made £30 on the book’s proceeds. Flush again, Williamson made his way for Scotland.

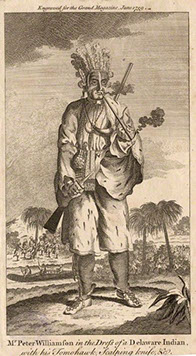

In a move that would have made P.T. Barnum proud, Williamson took to dressing as a Native American on his voyage north. He’d act out the customs of the Cherokee and other tribes he had run across in America as a platform to sell his autobiography. The shtick carried him all the way home to Aberdeen in June of 1758—fifteen years after he was abducted. Williamson’s hometown did not welcome their native son with open arms. The local constabulary charged him with libel saying Williamson was complicit in his kidnapping. Convicted of the charge, all the books he carried with him were burned and he was banished from Aberdeen as a vagrant.

Being banished was a minor affront compared to the troubles Williamson had seen throughout his life and he relocated to Edinburgh. There “Indian Peter” opened a coffee shop near the Parliament House and a few of his legal patrons encouraged him to sue the Aberdeen officials that tarnished his good name. Williamson won the lawsuit and collected £ 200 in damages plus £ 100 for legal fees. The notoriety from the court case, along with the cash award, allowed Williamson to open a number of business concerns. He set up a tavern near Parliament Close with a sign that read, “Peter Williamson, Vintner from the Other World” and a print shop in the Luckenbooths—neither far from Deacon Brodie’s workshop and home.

Possibly the greatest service, aside from his directory, Peter Williamson provided Edinburgh was establishing a postal service around 1773. The Williamson Directory advertised that he could dispatch letters and packages up to three pounds any place within a mile of Edinburgh’s Mercat Cross. Seventeen shopkeepers strategically selected throughout that radius were paid to receive letters and can be considered Edinburgh’s first post offices. Williamson’s postal system expanded and was the first regular and continuous postal system in Scotland. In 1793, Williamson’s postal system was incorporated into Great Britain’s General Post Office. (Evidently when England and Scotland merged with the Acts of Union in 1707, the English component felt it unnecessary for their Scottish brothers to have use of their mail system.) Williamson would die, possibly of complications from alcoholism, in 1799.

An engraving from the June 1759 edition of Grand Magazine depicting Peter Williamson in Native American attire.

Contact us

Notices