deacon brodie

The real story behind Edinburgh's most enduring legend

Deacon Brodie's legacy

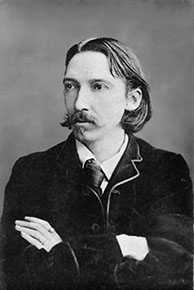

Aside from the pubs, in Edinburgh and other places, that capitalize on William Brodie’s history, by far the greatest legacy the Deacon left behind was his influence on Robert Louis Stevenson. Brodie’s story hit a resonate pitch with the author of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and the literary/popular culture convention of main characters exhibiting dualistic elements have fascinated audiences ever since. The story commonly told of Deacon Brodie infecting the mind of Robert Louis Stevenson can be found in Scottish Urban Myths and Ancient Legends by Sheena Blackhall and Grace Banks and goes as follows:

Louis Stevenson can be found in Scottish Urban Myths and Ancient Legends by Sheena Blackhall and Grace Banks and goes as follows:

Robert Louis Stevenson’s father had hired Brodie to make furniture for him; the man apparently inspired Stevenson to create the character of Jekyll and Hyde.

The story is quaint, but quite impossible as Stevenson’s father, Thomas, was born in 1818. Thomas would have had to have been one of Dr. Who’s companions to commission a piece of furniture from Brodie, who was executed in 1788. There is the possibility that the Robert Louis Stevenson’s grandfather, yet another Robert, had contact with Brodie. Grandfather Stevenson was a sixteen-year-old apprentice to his step-father, Edinburgh lamp maker Thomas Smith, at the time of Brodie’s hanging. Grandfather Stevenson’s vector to Brodie, if he ever met Brodie, would have been through Smith. The successful lamp maker might have commissioned a piece from Brodie’s workshop and/or had a professional relationship with Brodie. Grandfather Stevenson could have even purchased the cabinet secondhand at some later point in his life. It’s fairly probable that grandfather Stevenson attended Brodie’s hanging and would have seen the cabinet as a piece of Edinburgh’s history. The cabinet and grandfather Stevenson recounting of Brodie’s hanging would then have become part of the Stevenson’s collective pool of family story. Deacon Brodie could been the Stevenson’s answer to the boogieman and sparked subsequent Stevenson generations to eat their English peas.

The Edinburgh Writer’s Museum holds a cabinet in their collection that they believe is Robert Louis Stevenson’s inspirational Brodie-made cabinet. Denise Brace, a history curator for Edinburgh’s museums and galleries, indicates that there are no maker’s marks on the cabinet and the item’s providence comes from this letter attached in the cabinet’s wardrobe:

Made by William Brodie, Cabinetmaker, Edinburgh, with his own hands, about 1780. Brodie was Deacon Convenor (or President) of the Wrights, he was hanged in 1788, for a series of burglaries, culminating on an attack on the Government Excise Office, Chessel's Court.

Referred to in Deacon Brodie, or the Double Life by R. L. Stevenson & W. E. Henley: Act 1. Tableau 1. Scene 1: “there is the tall cabinet yonder; that it was that proved him the first of Edinburgh joiners, and worthy to be their Deacon and Head.” [Below this is a straight line and then]

Presented by R.L. Stevenson, on his departure for Samoa, To W.E. Henley. Sold by Mr. Henley’s executors in 1903, for £20, Bought by Lord Guthrie, in 1912, for £25

Without the benefit of a maker’s mark, it’s impossible to tell if the cabinet was made by Brodie or not, but for our purposes it does not matter who crafted the cabinet. This letter gives providence that Stevenson owned the cabinet and he believed it was made by Deacon Brodie.

Inspiration comes from the unlikeliest of places and the cabinet seems to be the catalyst for Robert Louis Stevenson’s fascination with the doggy Deacon. As a teenager Stevenson outlined a play based on Deacon Brodie’s life that was produced, with the assistance of English poet William Ernest Henley, in 1882. The melodramatic production of Deacon Brodie or the Double Life was a flop and had little to do with the historical circumstances of Brodie’s life. The play is so far afield from the actual events, the final act closes with William being killed in a sword duel the night of the Excises Office robbery. The list of historical sins in Deacon Brodie or the Double Life only spiral upward from this one example. Stevenson’s treatment of Brodie can be found on this site and is only recommended reading for those who are tracking the evolution of Robert Louis Stevenson’s writing.

fascination with the doggy Deacon. As a teenager Stevenson outlined a play based on Deacon Brodie’s life that was produced, with the assistance of English poet William Ernest Henley, in 1882. The melodramatic production of Deacon Brodie or the Double Life was a flop and had little to do with the historical circumstances of Brodie’s life. The play is so far afield from the actual events, the final act closes with William being killed in a sword duel the night of the Excises Office robbery. The list of historical sins in Deacon Brodie or the Double Life only spiral upward from this one example. Stevenson’s treatment of Brodie can be found on this site and is only recommended reading for those who are tracking the evolution of Robert Louis Stevenson’s writing.

The next set in the evolution of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde takes on a semi-mystical turn. The popular account is that Stevenson fell ill in September or October of 1885 and began to have dreams that formed the basis of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Stevenson quickly dashed off a manuscript for the book and gave the hard copy for his wife, Fanny, to read. Legend has that Fanny was so critical of Stevenson’s efforts, the ill and distraught author threw the manuscript in the fire.

The footprint of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and by extension that of Deacon Brodie, can even be seen influencing popular media of the last century. While not quantitative, one could safely say the themes in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde would make the “top ten list” of modern re-purposed classic literature pieces used in film and print. From Jerry Lewis’ The Nutty Professor to the Dan Aykroyd driven Doctor Detroit to Steven Moffett’s gritty 2007 reboot Jekyll, audiences constantly are enamored with Deacon Brodie inspired tales. One can even make the argument that the popularity of serial killer themed media stems from themes in Stevenson’s tale. Silence of the Lambs foil Hannibal Lecter is nothing more than a murderous Deacon Brodie. The same may be said of Psycho’s Norman Bates and the serial killer/blood spatter analyst Dexter Morgan.

Robert Louis Stevenson

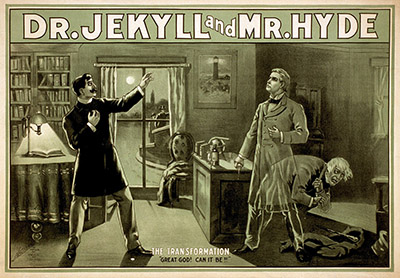

An 1880s poster promoting The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Contact us

Notices